Ms Gray had passion for her art, and as many passions come, it arrived accidentally one day as she walked along Dean St. in London: “She stumbled upon a lacquer repair shop and enquired if she could work there for a while. She spent most of the following months in the shop, watching and sometimes helping to rub down the many coats used to decorate screens and furniture. The next year, she returned to Paris armed with materials and the names of people who worked in the field. Soon, she met Seizo Sugawara, a penniless Japanese student in his 20s who had come to Paris to restore the lacquer pieces Japan had sent to the Exposition Universale. Gray asked him to teach her.” (Staunders, The House that Eileen Built.)

Ms Gray had passion for her art, and as many passions come, it arrived accidentally one day as she walked along Dean St. in London: “She stumbled upon a lacquer repair shop and enquired if she could work there for a while. She spent most of the following months in the shop, watching and sometimes helping to rub down the many coats used to decorate screens and furniture. The next year, she returned to Paris armed with materials and the names of people who worked in the field. Soon, she met Seizo Sugawara, a penniless Japanese student in his 20s who had come to Paris to restore the lacquer pieces Japan had sent to the Exposition Universale. Gray asked him to teach her.” (Staunders, The House that Eileen Built.)

Lacquer work is a noxious medium which causes Urushi-kabure or lacquer poisoning. The lacquer is extracted from the lacquer tree I would suspect much like maple syrup. The juice that comes out has a molasses consistency that turns black when it touches air. It is from this raw lacquer that the disease comes not only from direct contact but also from the fumes of its evaporation. As the raw lacquer is processed with filters and color, it becomes less toxic until eventually when it is applied to a surface and hardens; Urushi-kabure is generally no longer an issue. The disease is part of the craft, it is said that every lacquer worker would get the disease to some extent and build immunity—but this is most likely a myth as some workers would get the disease 5 or 6 times (Scheube).

After references in several articles that Gray had the lacquer disease and continued with her work; this literal physical suffering for ones art, made me wonder what were the symptoms exactly. It is not fatal but it is not particularly pleasant. The Diseases of Warm Countries: A Handbook for Medical Men, 1903 tells us of the following symptoms:

“A few hours after the poison has taken effect, the patient is in a slightly feverish condition and complains principally of itching and a disagreeable feeling of tension of the skin of the head, face and limbs. Soon after oedema of the affected parts of the skin sets in with catarrh of the contiguous mucous membranes…Small red papules rise on the oedematous skin; they gradually increase in size and small blebs with sero-perulent contents form on their apices. On the arms the eruption usually extends to the elbows, on the legs to the knees, and at these limits sharp lines of demarcation are perceptible. In men the scrotum and the prepuce always participate in the oedema, and in women the labia majors are similarly affected… The pustules, which frequently become confluent, dry up or burst and become covered with eschars, but large purulent ulcerations, may result” (Scheube, 331).

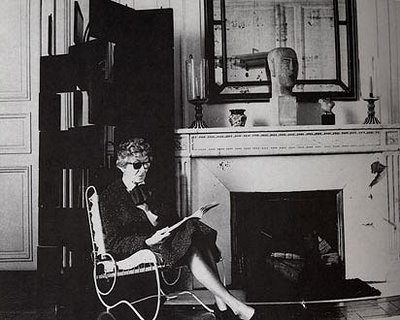

All reports say that Eileen Gray just had it on her hands, but she was a private person. In her passion she continued to work with it and would eventually master the lacquer process that earned her place in the history of great lacquer artists. (Staunders).

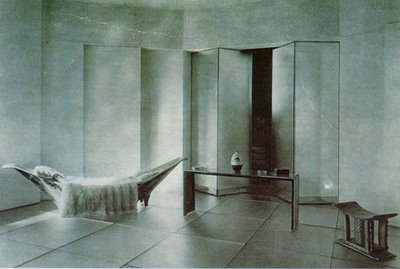

Ms Gray was not only a fine crafts person, but an architect, textile designer, interior designer, and furniture designer. Most designers won’t be remembered longer than the blink that occurs after paging though the latest addition of Met Home; Next! Especially, here in Los Angeles where real estate is marked up and moved on so quickly such as fashion and prevailing taste–the transitory nature of interiors. I would call Eileen Gray my new design hero but I would hate to sound retrospect.

Oh man I haven’t read your blog for ages. Forgive me I know not what I do (not do).

Once, I decided to write a large, complex research paper about one of the lacquer Buddhas at the Met for an art history class.

Ambitiously, I envisioned arguing that the genus of one particular Buddha’s lacquer wasnt neccessarily the Rhus vernicifera, since the particular statue i was writing about came from a region of China with other sumacs that also produce lacquer-worthy urushiol. I wanted to frame the story around the British plant collector for whom the sumac tree that I was proposing the Buddhas lacquer was made of. It was genius.

Except that I was way over my head and after involving the head of art conservation at the Met (one of DB’s friends) and several prominant Academians, I wrote a bad lazy paper of which have never spoken of until now.

Also, I am violently allergic to urushiol. And I’m coming to LA tomorrow and I can’t find your cell number.